Maintaining

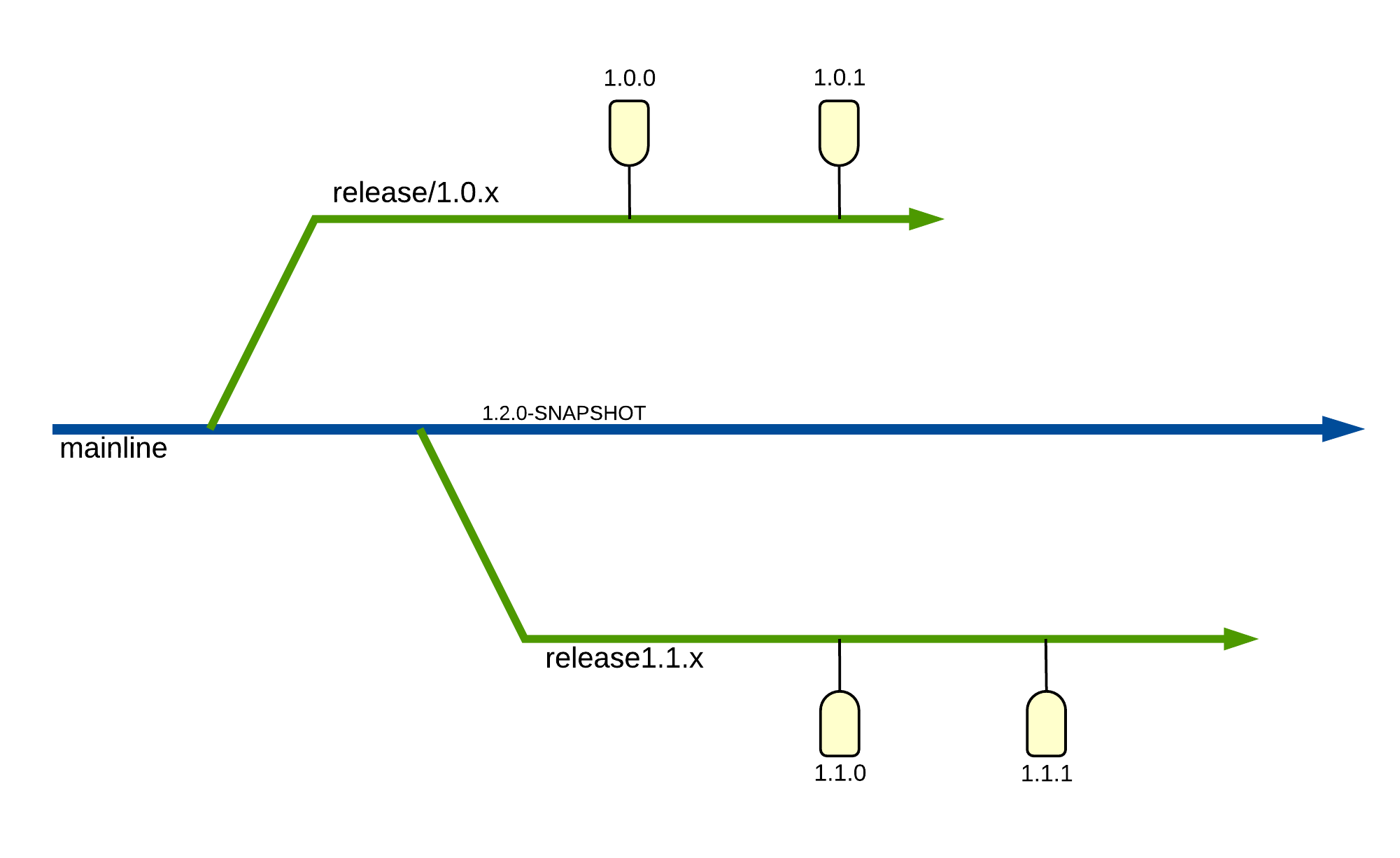

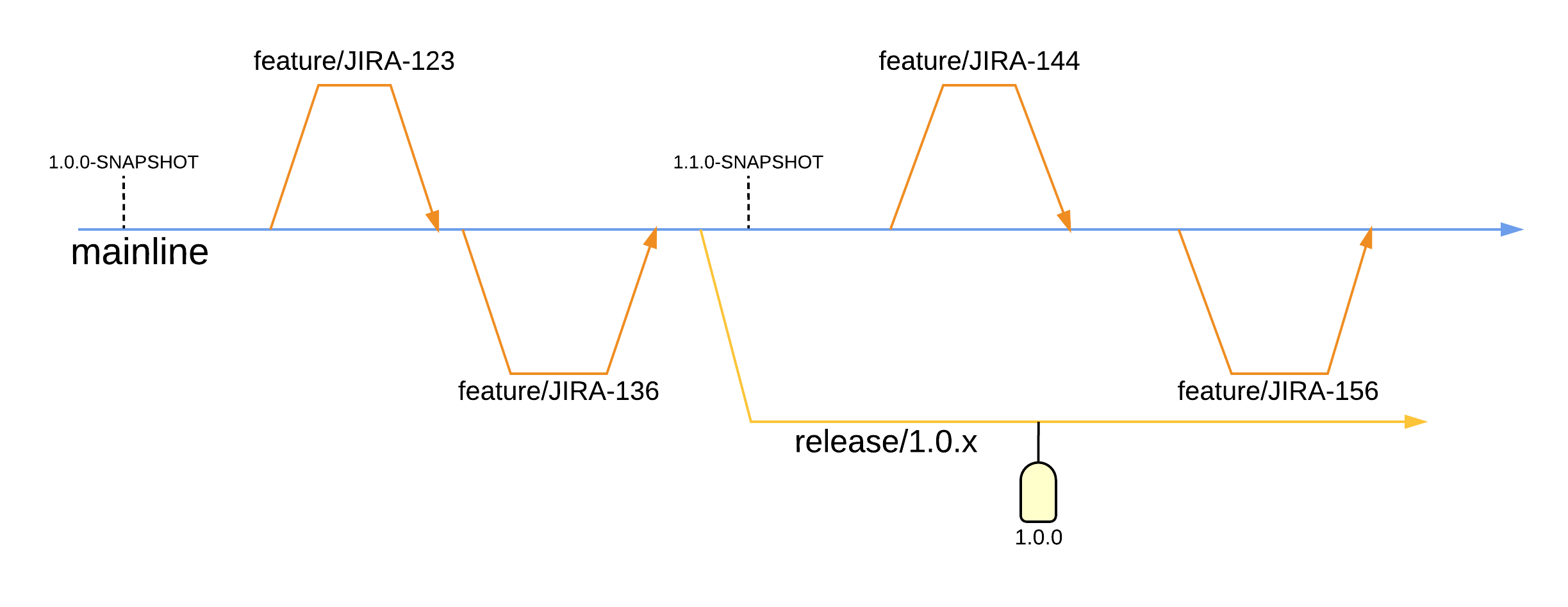

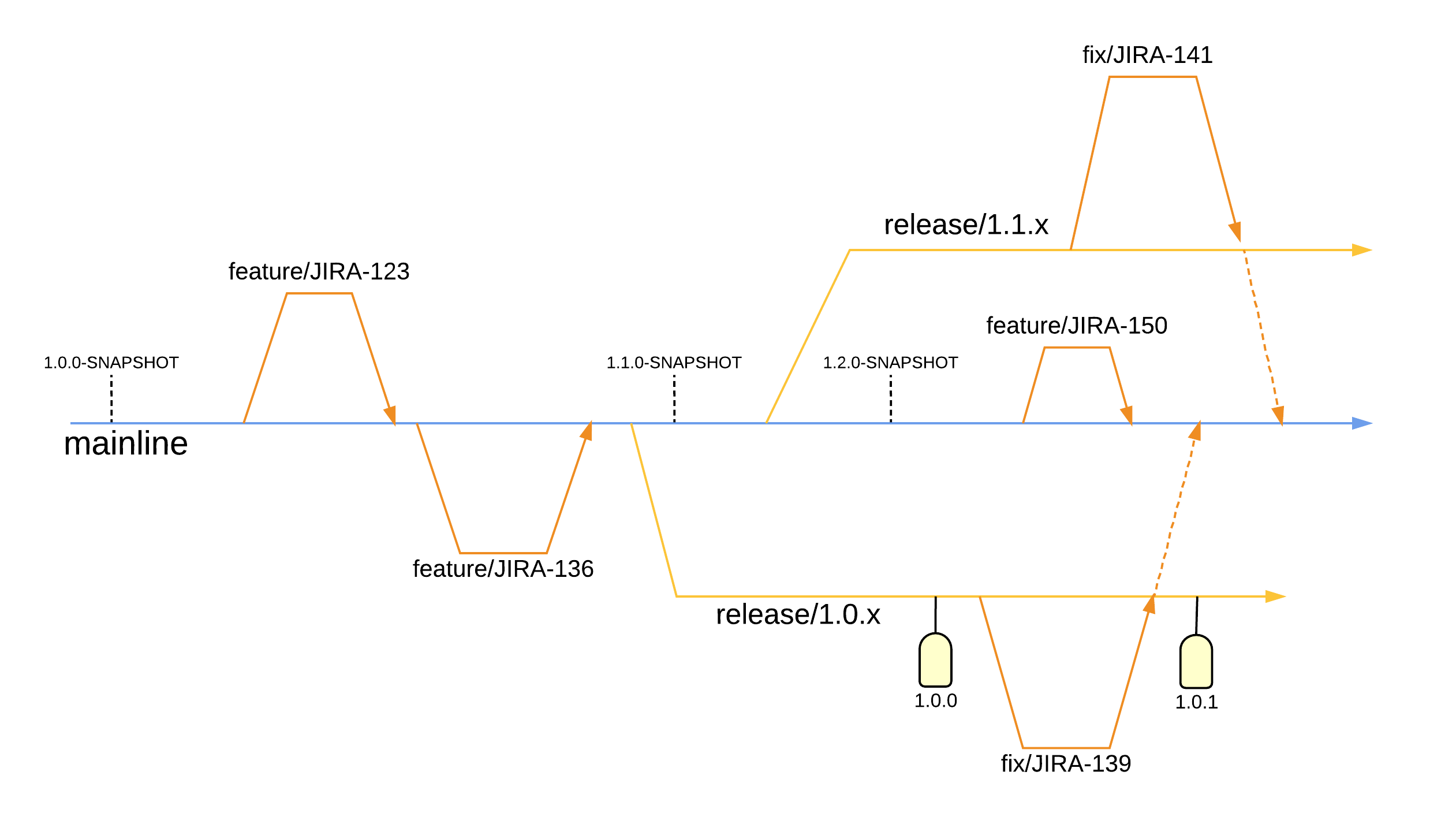

Branching for maintenance

How do I... ?

You may wonder if there are some maintenance scenarios that releaseflow might not support. After all, it's a simple strategy. Perhaps there are some more complex use cases that aren't supported? We've not uncovered such a problem so far. Here are a few "How do I..." questions and answers which might just help settle your nerves.

How do I find the code running in production?

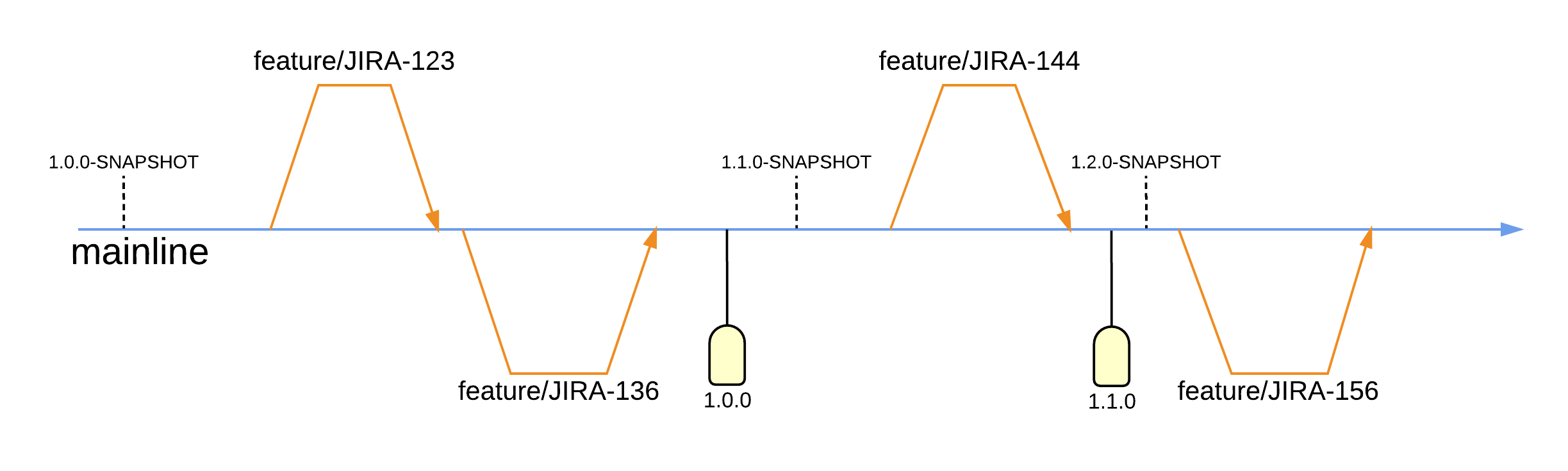

Each release has a corresponding tag. To find the exact code running in production one simply needs to determine the version of the application deployed. Once known, the corresponding tag can be used to navigate to the code at the exact commit deployed in production.

How do I fix a defect?

Similarly to adding a new feature, the starting point must be determining the target of the defect. Next, a new branch should be created from the target with a name referencing the defect such as fix/DE1234. The defect remedial action should take place on this branch and result in a merge request to have the fix applied to the target branch. Finally, the merge request reviewers should also ensure this fix is applied (usually cherry-picked) to other branches where necessary, e.g. master and/or ongoing release branches. How do I ensure a defect fix is applied to future/past versions? As above, the merge request reviewers should also ensure this fix is applied (usually cherry-picked) to other branches where necessary, e.g. master and/or ongoing release branches.

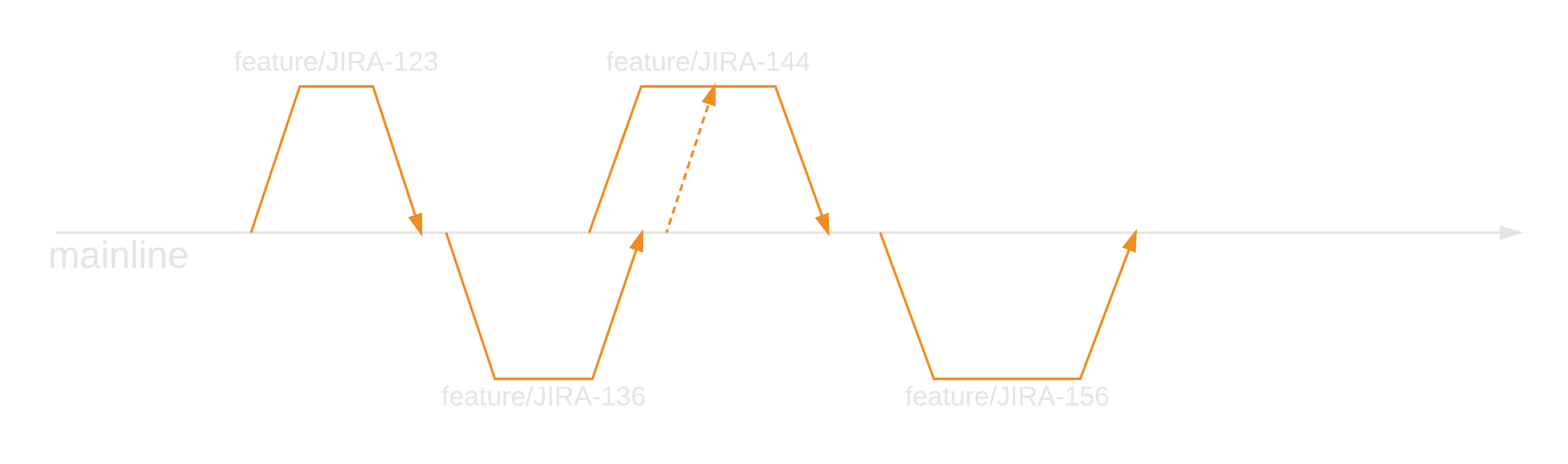

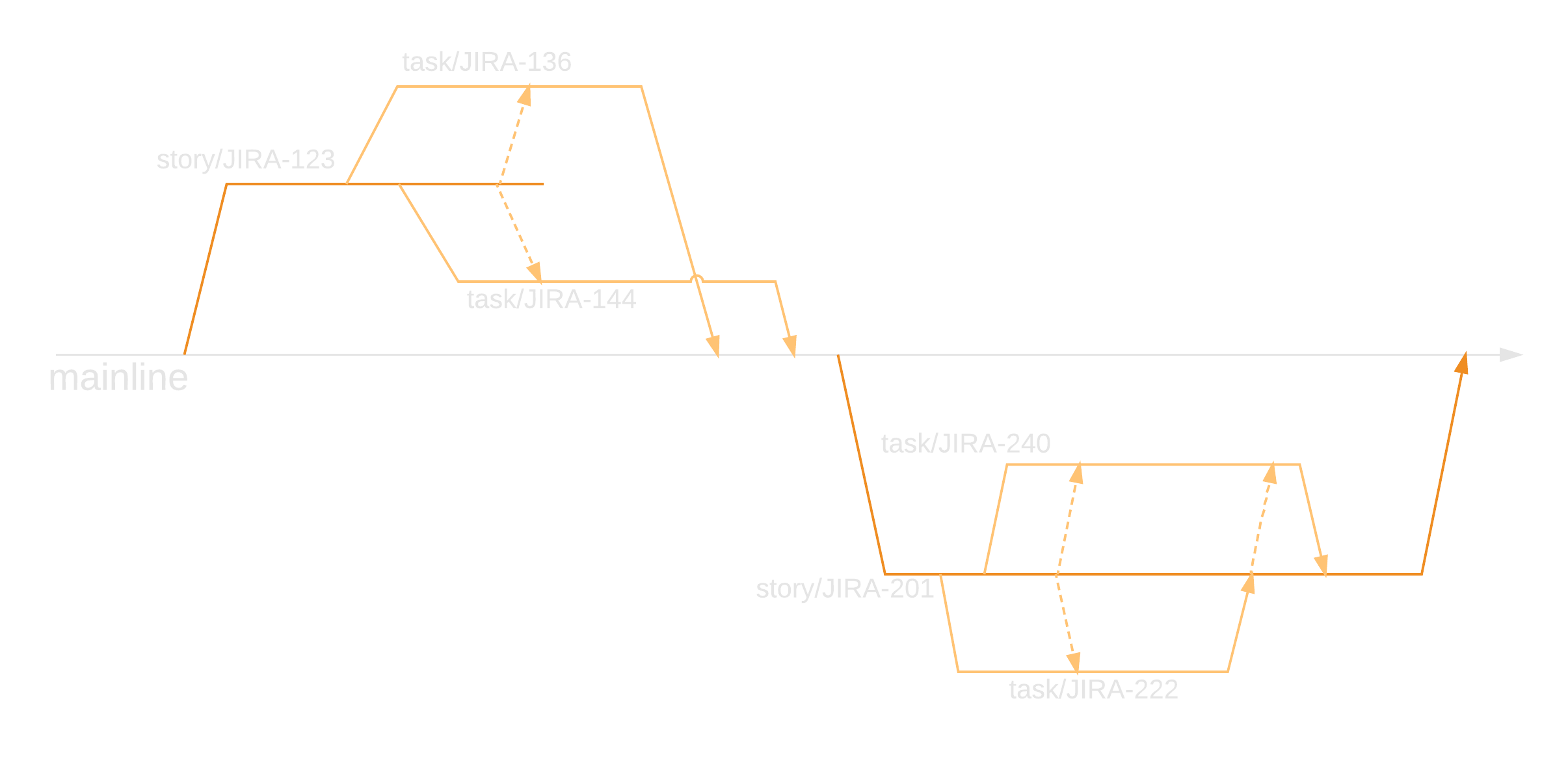

How do I add a new feature?

Firstly, one must determine the target of a new feature. This will usually be master where the latest development is in motion. Of course, if the feature is to target a specific release, then the corresponding release branch should be sought out. Secondly, a new branch should be created from the target. The branch should be given a useful name, usually a user story reference with a feature prefix, i.e. feature/US1234. Thirdly, feature work should happen on this branch and finally a merge request should be raised to have the feature pulled into the target branch.